Close

It is instinctual to protect children from the difficult realities of death, dying and grief, far beyond what their young selves should have to bear. But for Brayan Tan, who was not allowed to attend the cremation when his grandmother passed, it was a missed opportunity for a last goodbye. “My mum didn’t let me go to the cremation because I was only seven at that time,” Brayan, who is now 11, shares in the video above. “I was very sad because the wake was the last time I was going to see her.”

“I think it’s helpful for children to see the wake and cremation or burial because they will see that their family member’s or relative’s body was not harmed, and it will assure them that they will rest in peace.”

Brayan’s candid insights are a stark reminder that children often know more than adults give them credit for, and avoidance can cause more harm than good, even if well-intended.

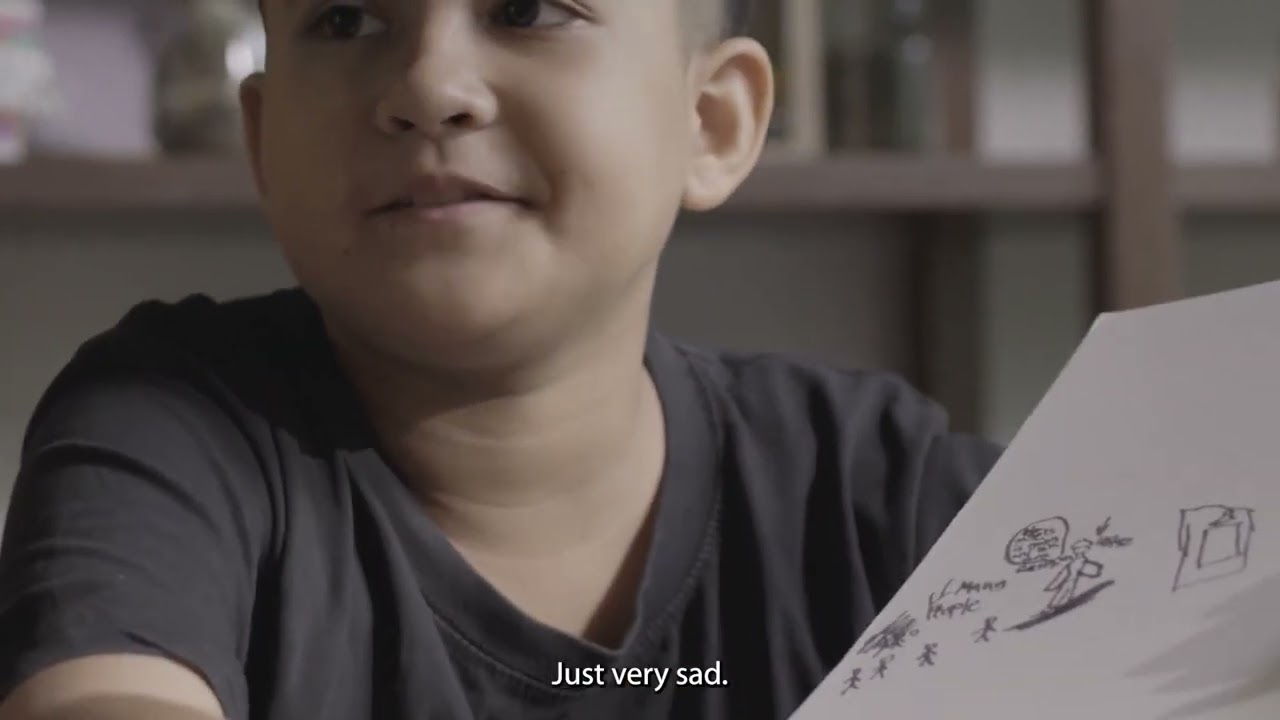

Azka Mizah, 10, attended his grandfather’s burial, an experience he remembers vividly. Gesturing to a picture he drew of the scene, he says, “This is my grandfather, he was put inside the grave,” he shares. “This is me here, just very sad. I just miss him, but I’m happy because now he is with God.”

Flights of Fantasy

Depending on their age, children often do not have a complete understanding of death and dying. For very young children under the age of six, they may not register that a loved one has passed, if they are still able to see and touch the deceased. Reality often sets in only after they are no longer able to see their loved one.

The situation is often exacerbated by a lack of age-appropriate information, which leads children to filling the void with potentially dangerous misconceptions. “When our patient, Susan*, was diagnosed with end-stage cancer, her son, Adam*, believed that his misbehaviour had caused her to fall ill,” shares Gracia Lim, HCA Medical Social Worker and Programme Lead of Project Kindle. Gripped with grief and guilt, the young boy believed he would be punished when his mother passed on.

Other children may develop paranoia about their own health, believing that they are dying if they have a simple flu or cold.

Oftentimes, their parents and adults around them may not even realise the full extent of their erroneous and misguided beliefs. In the case above, Susan had perceived Adam to be coping well with the news of her illness, and his father, similarly, did not think he would understand what cancer was.

But secrecy and assumptions are detrimental to children, who are already frightened and confused by the events unfolding before them. Only by opening the Treasure Box of the myriad questions children have, can we demystify death and dying.

What would be in your child’s Treasure Box?

*not their real names

This candid, non-scripted video is part of the Straight Talk series, launched by HCA under Project Kindle, an initiative that aims to support young families in coming to terms with death and dying.

It is instinctual to protect children from the difficult realities of death, dying and grief, far beyond what their young selves should have to bear. But for Brayan Tan, who was not allowed to attend the cremation when his grandmother passed, it was a missed opportunity for a last goodbye. “My mum didn’t let me go to the cremation because I was only seven at that time,” Brayan, who is now 11, shares in the video above. “I was very sad because the wake was the last time I was going to see her.”

“I think it’s helpful for children to see the wake and cremation or burial because they will see that their family member’s or relative’s body was not harmed, and it will assure them that they will rest in peace.”

Brayan’s candid insights are a stark reminder that children often know more than adults give them credit for, and avoidance can cause more harm than good, even if well-intended.

Azka Mizah, 10, attended his grandfather’s burial, an experience he remembers vividly. Gesturing to a picture he drew of the scene, he says, “This is my grandfather, he was put inside the grave,” he shares. “This is me here, just very sad. I just miss him, but I’m happy because now he is with God.”

Flights of Fantasy

Depending on their age, children often do not have a complete understanding of death and dying. For very young children under the age of six, they may not register that a loved one has passed, if they are still able to see and touch the deceased. Reality often sets in only after they are no longer able to see their loved one.

The situation is often exacerbated by a lack of age-appropriate information, which leads children to filling the void with potentially dangerous misconceptions. “When our patient, Susan*, was diagnosed with end-stage cancer, her son, Adam*, believed that his misbehaviour had caused her to fall ill,” shares Gracia Lim, HCA Medical Social Worker and Programme Lead of Project Kindle. Gripped with grief and guilt, the young boy believed he would be punished when his mother passed on.

Other children may develop paranoia about their own health, believing that they are dying if they have a simple flu or cold.

Oftentimes, their parents and adults around them may not even realise the full extent of their erroneous and misguided beliefs. In the case above, Susan had perceived Adam to be coping well with the news of her illness, and his father, similarly, did not think he would understand what cancer was.

But secrecy and assumptions are detrimental to children, who are already frightened and confused by the events unfolding before them. Only by opening the Treasure Box of the myriad questions children have, can we demystify death and dying.

What would be in your child’s Treasure Box?

*not their real names

This candid, non-scripted video is part of the Straight Talk series, launched by HCA under Project Kindle, an initiative that aims to support young families in coming to terms with death and dying.